When we toss a plastic container into the recycling bin, most of us harbor a hopeful belief that it will magically transform into a new and eco-friendly product. After all, recycling is synonymous with reducing waste, conserving resources, and boosting the economy, right? Well, not exactly. We’re doing more Wishcycling than we are recycling.

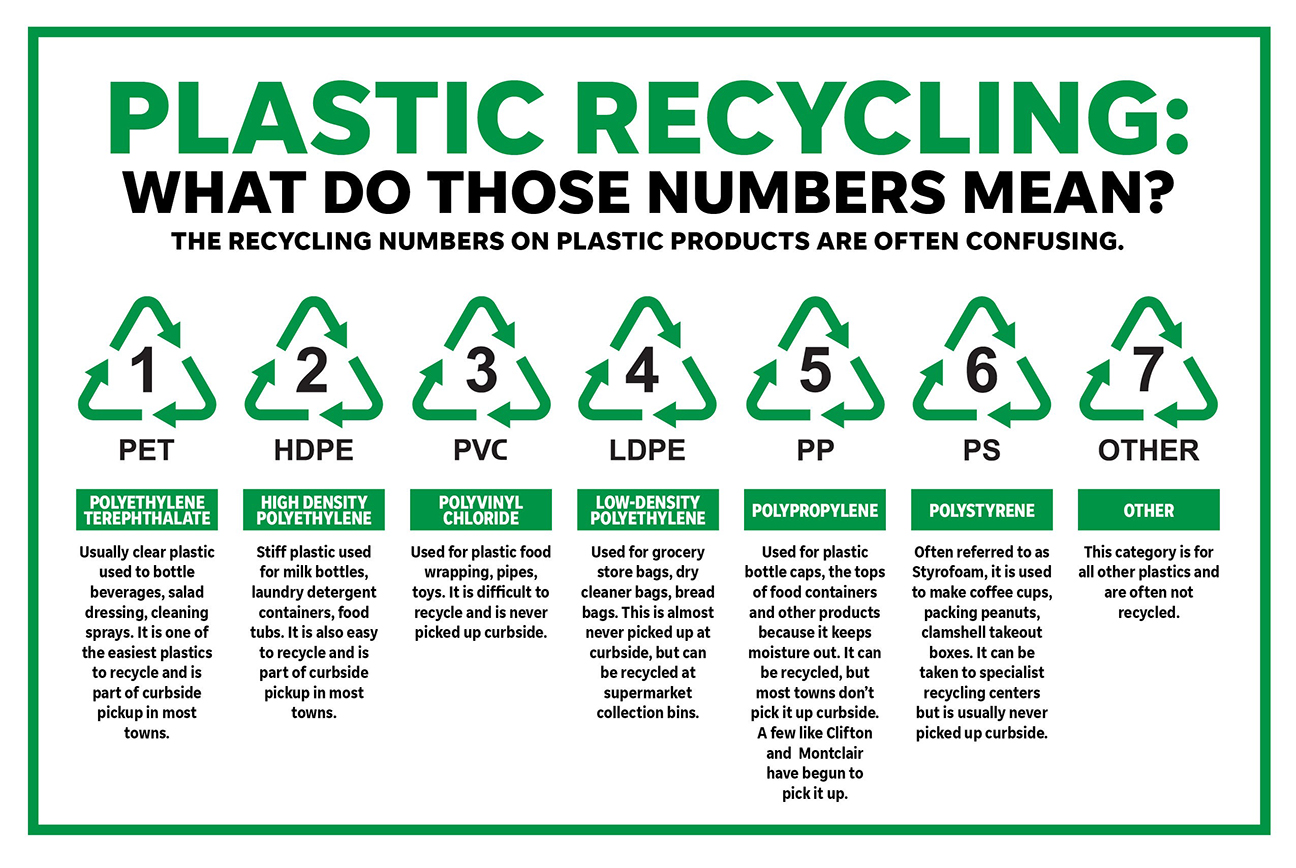

The truth about “recyclable” plastic is far from what most people assume. That little triangular symbol with chasing arrows on the bottom of plastic containers doesn’t mean what you might think. It’s not a guarantee of recyclability; rather, it’s an identification code specifying the type of plastic used.

Regrettably, even plastics that are technically recyclable often don’t get recycled. For instance, plastics marked with a PET No. 1 symbol (commonly seen on water or soda bottles) or a HDPE No. 2 symbol (found on milk jugs or shampoo bottles) sometimes find their way into the recycling process.

However, a 2017 report from a plastics industry trade group revealed that only approximately 21% of PET plastic collected for recycling is actually repurposed into new products. A more recent 2022 Greenpeace report estimates that the reprocessing capacity for HDPE plastic is even lower, hovering around 10%.

As for plastics labeled with Nos. 3 through 7, the reality is grim: they are rarely recycled at all. Those salsa tubs, coffee cup lids, takeout containers, and cold drink cups are often destined for a landfill or incinerator, regardless of the number inside the triangle.

In response to this issue, California passed a law in 2021 mandating a study on materials actually recycled in the state and prohibiting the use of the chasing arrows symbol on non-compliant products. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency also requested the Federal Trade Commission to enforce stricter regulations, requiring products to prove a “strong end market” for recycling before displaying the symbol.

The core problem lies in the inherent difficulty of recycling plastic. With numerous plastic types in circulation, sorting through them becomes an expensive and monumental task. The recycling process itself is complex and costly, leading the industry to opt for manufacturing new plastic as the more economical choice.

Moreover, plastic recycling often generates microplastics that infiltrate the environment, and the reprocessing can release toxic emissions. In many cases, our attempts to recycle plastic inadvertently harm the environment.

So, where does all this plastic go? Sadly, much of it ends up in landfills, incineration facilities, or even the ocean, contributing to phenomena like the Pacific Garbage Patch. The wishful belief in plastic’s recyclability has led to the practice known as “wishcycling” – putting various plastics, including non-recyclables like bags and plastic wrap, into recycling bins out of a mix of hopefulness and reluctance to confront reality.

This wishcycling trend complicates the work of local recycling centers, making the sorting process less efficient and more costly. Consequently, recycling other materials like glass and aluminum becomes challenging.

The solution is clear, albeit not easy: we must drastically reduce our consumption of plastic, especially single-use plastic. While plastic offers convenience and cost savings, our over reliance on it has led to environmental challenges. By consciously choosing non-plastic alternatives and being mindful of our consumer choices, we can collectively make a difference in reducing plastic waste and its impact on the environment.