The state of Rhode Island is about the size of a landfill. The state’s efforts to combat plastic pollution have seemed commendable for a state so tiny, with bans on polystyrene food containers, plastic straws, and single-use plastic bags, however, recent revelations point out that these measures barely scratch the surface of the state’s mounting plastic waste problem. After all, plastic waste is still a dilemma, and Rhode Island, like virtually every other state, is making empty promises, diverting funds toward more profitable options and lining pockets while burying the truth. Plastic is building up in landfills and no one is working to stop it.

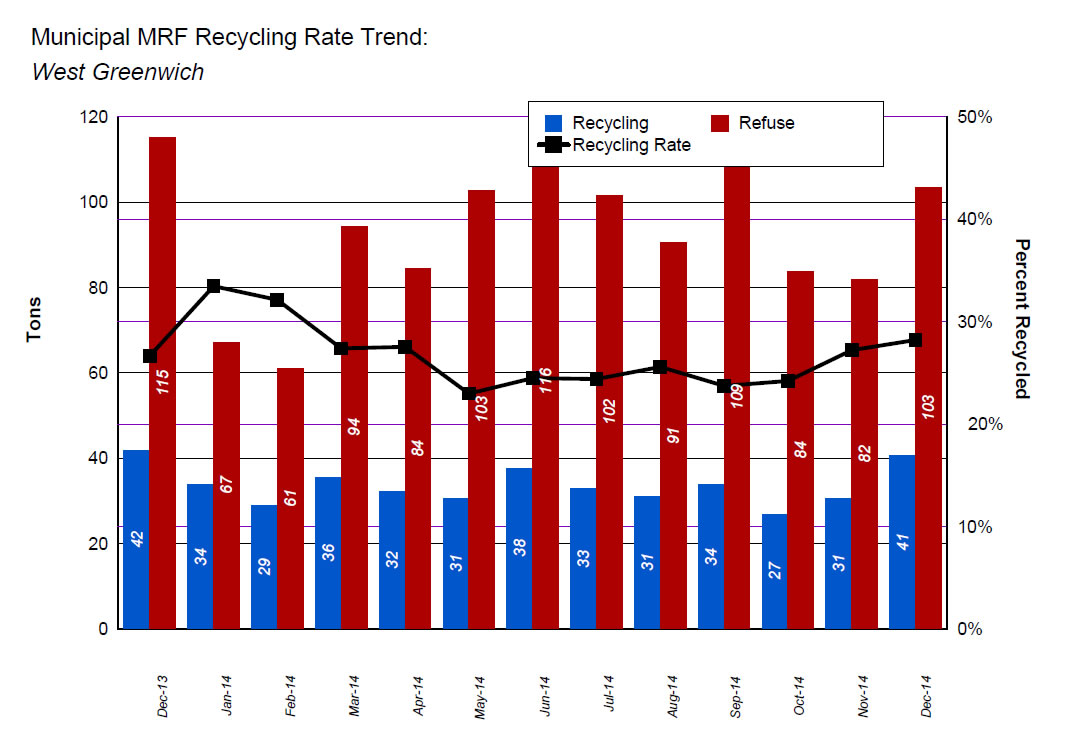

A joint report from the state Department of Environmental Management and the Rhode Island Resource Recovery Corporation (RIRRC) unveiled a sobering reality: the majority of plastic material in Rhode Island isn’t being recycled but rather buried in landfills alongside other waste. Shockingly, approximately 73% of all plastic material ends up in landfills, amounting to over 26,000 tons annually. Only a fraction, about 7,000 tons, undergoes recycling at RIRRC’s materials recovery facility.

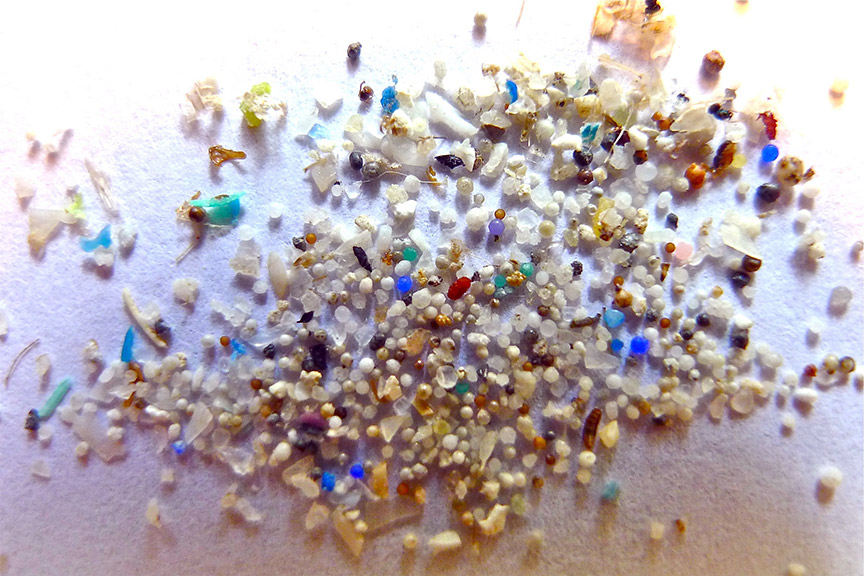

The consequences of this plastic waste are tangible. A 2023 study conducted by the University of Rhode Island revealed that the Narragansett Bay seafloor is laden with over 1,000 tons of microplastics accumulated over the past two decades. Sounds like a great place to fish and swim. Furthermore, litter, including ubiquitous single-use items like nip bottles, poses a growing threat to the environment and public health.

Compounding these challenges is the impending deadline facing RIRRC’s Central Landfill in Johnston, which is projected to reach full capacity by 2040. However, viable alternatives for waste management post-landfill cost money and take effort to produce, presenting policymakers with a pressing dilemma – “should we spend the money or take the time?”

Jed Thorp, executive director of Clean Water Action Rhode Island, emphasizes the need for greater understanding of plastic’s environmental impact and advocates for a container deposit law, commonly known as a bottle bill. Such legislation, already implemented in neighboring states like Connecticut and Massachusetts, incentivizes plastic recycling and reduces litter by offering refunds for returned containers.

Despite the potential efficacy of a bottle bill, legislative action has been more than sluggish. Rep. Carol McEntee’s repeated attempts to introduce bottle bill legislation have been stymied, with the debate overshadowed by alternative proposals like a “producer tax” on beverage containers, where the state spends nothing in bottle return refunds but rather taxes manufacturers while still avoiding the responsibility of dumping plastic into landfills. Taxation doesn’t stop waste.

In lieu of decisive action, lawmakers established a study commission, at a cost, to explore the feasibility of a bottle bill further instead of taking action on the proven discoveries already made. However, time is of the essence, with Thorp stressing the urgency of completing the commission’s work to inform legislative action promptly.

Drawing parallels to similar initiatives in California, where promises of change consistently fall short, Rhode Island faces a critical juncture in addressing its plastic waste crisis. California has shown that in the final hours, politicians manage to make empty promises of change to benefit recycling and plastic waste efforts, but somehow those new promises rarely come to light. Take Senate Bill SB54, which was signed in the last minute before Californian’s Against Waste were to back a ballot measure to reduce single-use plastic waste. The promising talk has had little effect. SB 54 fails to address concerns regarding the extraction, refinement, production, consumption, and waste of plastic pollution.While legislative maneuvers and study commissions offer potential pathways forward, tangible progress remains elusive as plastic waste continues to proliferate the landscape. With a national leader like California taking such little responsibility, who expect Little Rhodie to be any different.

Ultimately, the flow of plastic waste through the state persists unabated, highlighting the imperative for Rhode Island to prioritize comprehensive and effective measures to safeguard the environment and promote sustainable waste management practices. As 2024 rolls along, environmental advocates are expecting to see little change.