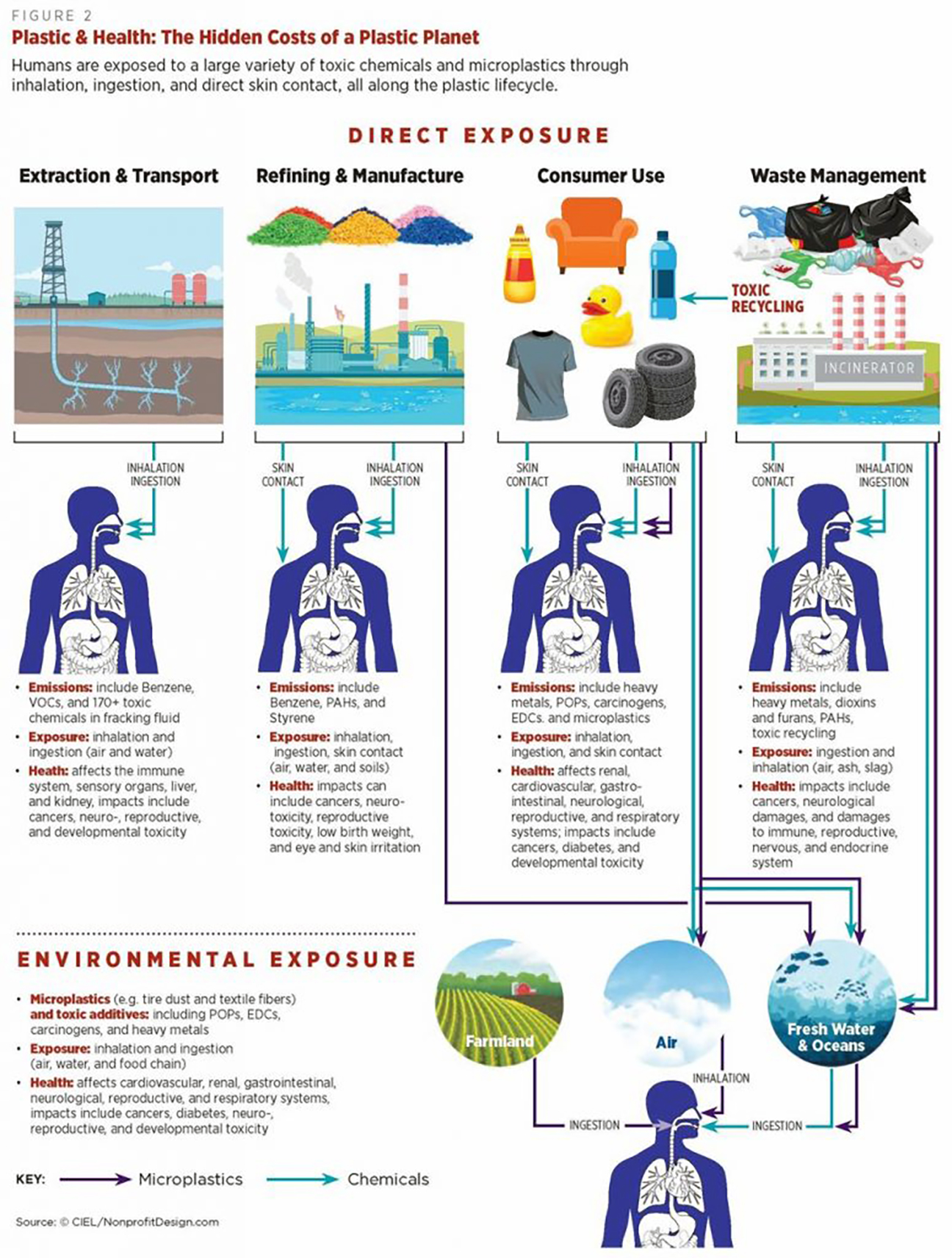

Plastic, a revolutionary invention over a century ago, has woven itself into the very fabric of our environment. From the ocean depths to the Arctic sea ice, from the French Pyrenees’ atmosphere to the human bloodstream, its omnipresence is undeniable. However, a recent study led by scientists from the University of Gothenburg in Sweden delivers a disconcerting revelation: recycled plastics harbor hundreds of toxic chemicals and compounds, rendering them unsuitable for most purposes and jeopardizing the vision of a circular economy.

Plastics, notorious for their persistence in the environment, can take hundreds of years to break down. Adding to this concern are per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), commonly known as “forever chemicals,” embedded within plastics, which boast an even more prolonged degradation period. The new study, titled “A dataset of organic pollutants identified and quantified in recycled polyethylene pellets,” exposes the extensive range of toxic elements present in recycled plastics, including pharmaceutical drugs, pesticides, and industrial compounds.

The researchers assert that this chemical complexity poses a significant obstacle to building a circular economy. The study emphasizes that plastics are produced with a myriad of chemical compounds, some of which are known to be hazardous, while others lack comprehensive hazard data. Additionally, non-intentionally added substances can contaminate plastics at various stages of their lifecycle, resulting in recycled materials with an unknown number of chemical compounds at unknown concentrations.

The study, published in the journal Data in Brief, unveils a concerning reality: less than 1% of plastics chemicals are subject to international regulation, leaving a vast majority unmonitored. The upcoming third meeting of the Plastics Treaty Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee, scheduled for November 13-19 in Nairobi, Kenya, will provide a platform for scientists, environmental advocates, and delegates to discuss recent scientific findings affirming that no plastics can be deemed safe or suitable for reuse or regeneration due to their toxic chemical content.

Bethanie Carney Almroth, a professor at the University of Gothenburg, underscores the challenges associated with plastic recycling and toxic chemicals. While touted as a solution to the plastics pollution crisis, the study reveals that toxic chemicals within plastics complicate their reuse, disposal, and hinder recycling efforts. The international research team conducted tests on plastic pellets from recycling plants across 13 countries, unveiling a staggering 491 organic compounds, with an additional 170 provisionally annotated.

With over 13,000 chemicals employed in plastics, a quarter of which are classified as hazardous, the study concludes that “no plastic chemical [can be] classified as safe.” The unregulated nature of chemical compounds used in plastics manufacturing, coupled with the complexities of the international plastics waste trade, further exacerbates the problem. Urging a rapid phase-out of plastic chemicals that pose risks to human health and the environment, Carney Almroth emphasizes the need for concerted efforts to address this looming threat. As discussions unfold at the Plastics Treaty summit, the study adds a compelling dimension to the urgency of reevaluating our reliance on plastics and forging a sustainable path forward.